Chapter 3 Introduction to Somatic Evidence Types in Cancer

3.1 Learning Objectives

This chapter will cover:

- Three Somatic Clinically Actionable Evidence Types

- Functional Evidence Based on Muller’s Morphs

- Oncogenic Evidence Based on The Hallmarks of Cancer

3.2 Somatic Clinically Actionable Evidence Types

While germline classification of variants has focused on the link between disease causality and the variant, arguably the most important classifications for somatic tumor variants are based on clinical actionability. The main categories of clinical actionability are Predictive/Therapeutic, Diagnostic, and Prognostic.

Predictive/Therapeutic evidence about a variant is associated to drug sensitivity induced by the variant in the tumor. This sets up the potential for targeted therapy, where in the ideal scenario, cells carrying the somatic variant are sensitized to drug treatment, but cells without the variant are unaffected. This model exploits the oncogene addiction mechanism, where inhibiting activity of a driver mutation will induce cell death. In reality, off target effects will often be induced due to a wider spectrum of inhibition by the drug, which is usually against kinase activity, as well as other off target biological effects.

Prognostic evidence associated to a variant captures the general effect of a variant on patient outcome, ideally independent of treatment type. If it is seen within a general population of patients with a certain cancer type, that patients with a given variant do better (or worse) than patients without the variant, then this would be evidence supporting a positive (or negative) prognostic effect of the variant in this disease type.

Diagnostic evidence captures the role a variant in distinguishing disease subtypes. Governing bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) produce guidelines for disease classification which often incorporate the presence or absence of specific variants as diagnostic inclusion or exclusion criteria.

3.3 Somatic Functional and Oncogenic Evidence Distinction

The discussion of functional evidence and oncogenic evidence in the next section will closely mirror the way these types of evidence are handled in the CIViC knowledgebase (Danos et al. 2019), which will be discussed in a later chapter. Other knowledgebases, such as OncoKB (Chakravarty et al. 2017) make similar distinctions between oncogenic and functional evidence

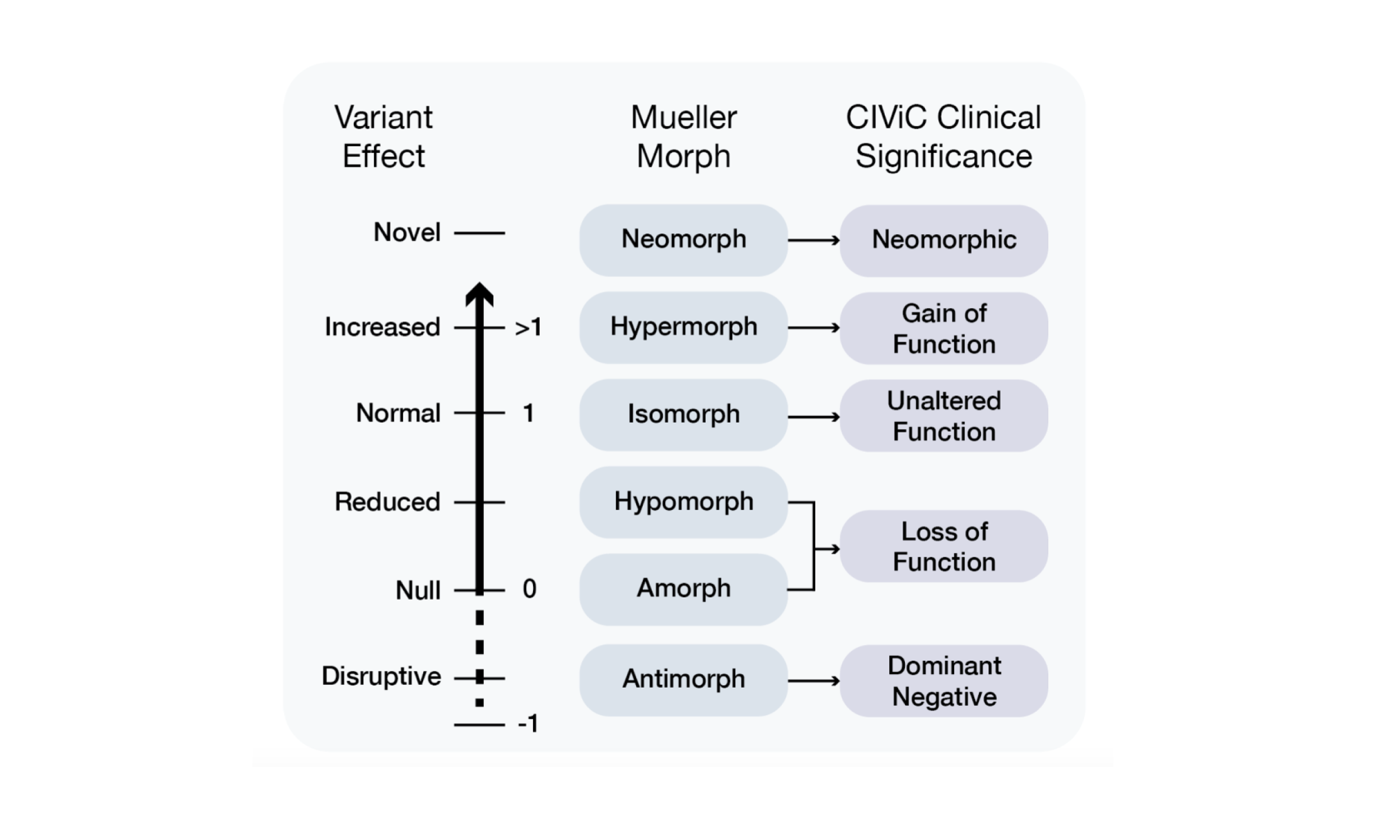

3.3.1 Functional Evidence and Muller’s Morphs

Somatic Functional Evidence is often derived from (or inspired by) the Morphs of Muller, originally inferred from work in fly model systems. This system of functional evidence classification and annotation consists of six terms. Isomorphic variants cause no alteration to the protein function. Hypermorphic variants cause a gain of function (increased function) for the variant. Hypomorphic variants cause a reduced protein function, and amorphic variants cause a total loss of function. Neomorphic variants induce novel function to the protein that would otherwise not be present. These annotations are usually drawn from in vitro functional assays that measure protein activity instead of the effect of the variant on behavior of the cell, such as increased growth, or immunity to apoptosis.

3.3.2 Oncogenic Evidence and The Hallmarks of Cancer

The oncogenicity of somatic variants is an additional evidence type that can play an important role in determining the clinical usefulness of a mutation. Variants that are shown to have oncogenic driver potential may also have clinical utility. Evidence is considered oncogenic when it demonstrates that the variant contributes to the appearance of one or more of the Hallmarks of Cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011) in cells. Demonstration that a novel variant is oncogenic can have clinical impact in some cases. For instance if a non small cell lung carcinoma has an unknown EGFR variant, but this variant can be shown to be oncogenic, then existing tyrosine kinase inhibitors established to target EGFR driver mutations are recommended to use. In contrast demonstration of a somatic variant to be a passenger (benign) mutation is also of important value in some cases. For instance the presence of KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer are a counterindication for use of EGFR inhibitors for treatment. But in the case of an unknown KRAS mutation in colorectal cancer, if it can be shown to be benign, then EGFR inhibition could potentially still be recommended.